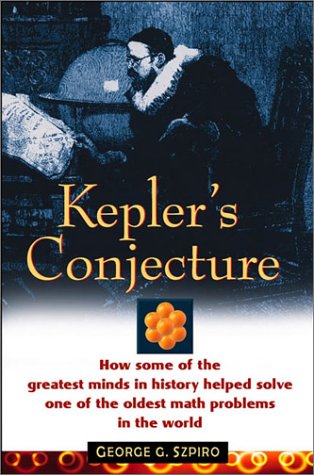

| Sir Walter Raleigh simply wanted to know the best and most efficient way to pack cannonballs in the hold of his ship. In 1611, German astronomer Johannes Kepler responded with the obvious answer: by piling them up the same way that grocers stack oranges or melons. For the next four centuries, Kepler's conjecture became the figurative loose cannon in the mathematical world as some of the greatest intellects in history set out to prove his theory. Kepler's Conjecture provides a mesmerizing account of this 400-year quest for an answer that would satisfy even the most skeptical mathematical minds. For 400 years, some of the best and brightest minds set out to prove Kepler's conjecture -- like Fermat's celebrated last theorem, one of the oldest unproven mathematical conjectures -- which raised one perplexing question: What is the best way to pack balls as densely as possible? Kepler's Conjecture traces the fascinating history and progression of this geometric puzzle, illustrating how thoroughly this one simple question stymied the mathematical world. Sometime toward the end of the 1590s, English nobleman and seafarer Sir Walter Raleigh set this great mathematical investigation in motion. While stocking his ship for yet another expedition, Raleigh asked his assistant, Thomas Harriot, to develop a formula that would allow him to know how many cannonballs were in a given stack simply by looking at the shape of the pile. Harriot solved the problem and took it one step further by attempting to discover how to maximize the number of cannonballs that would fit in the hold of a ship. And thus a problem was born. After contemplating the question for a while, Harriot turned to one of the foremost mathematicians, physicists, and astronomers of the time, Johannes Kepler. Kepler did not reflect long, and came to the conclusion that the densest way to pack three-dimensional spheres was to stack them in the same manner that market vendors stack their apples, oranges, and melons. Although this was fine for fruit vendors, until the conjecture could be proven, the mathematical world could not accept it. The first and only popular account of one of the greatest math problems of all time, Kepler's Conjecture examines the attempts of many mathematical geniuses to prove this problem once and for all -- from Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe to math greats Sir Isaac Newton and Carl Friedrich Gauss, from modern titans David Hilbert and Buckminster Fuller to Thomas Hales of the University of Michigan, who in 1998 submitted what seems to be the definitive proof. |